I really didn’t know what to expect when I joined our first Zoom class in August—a mere 4 months ago in calendar time and closer to 40 years ago in experienced time. How would I adjust to being in school after being so long away from it; how would grad school be different from college; how would remote learning even work? I was stumbling every time I even tried to describe what Digital Humanities (DH) was when people asked me what I was studying. “You know, like humanities, but digital.” Little did I know…

The vast scope of our readings, our care-full and engaging conversations, the most amazing and thoughtful and socially justice–minded project presentations everyone gave—I’m in awe of all of us and what we accomplished together. Thank you doesn’t fully cover it, but THANK YOU so much for everything. I can’t imagine a better introduction to the program, and I am beyond excited to start building our projects together next semester.

As others have mentioned, this final project felt very daunting. What do I know? I’m a little into the macabre, and I just wanted to map a few cemeteries, and I don’t even know that much about mapping. Am I really adding to the field at large? So I admit I called on my old friend procrastination, and I procrastinated. And then procrastinated a little more, for good measure. But even as I was putting off actually writing, ideas were stewing in my head.

And I’m so grateful to Prof. Gold for introducing me to a student further along in the program who is also interested in cemetery studies. She was so supportive and encouraging in our conversation, and she helped me realize there is indeed a place for my mapping idea in DH. And she led me to a recent anthropology dissertation from a Graduate Center alum about the historical deathscape of New York City from the colonial period onward. And that got me thinking, maybe it’s not too late, there really are a wealth of resources available within the GC. The mapping part of my mapping project was throwing me for a loop, and I remembered that Olivia Ildefonso led an intro to ArcGIS workshop, and as a digital fellow she offers consultations. And I’m so grateful to her for fitting me in last-minute at the end of the semester. She really helped me think about what my data set could look like and helped me reign in my scope creep. (At least I think she did; Matt, if scope creep is still an issue in my final proposal, just know that it was WAY worse in earlier drafts.)

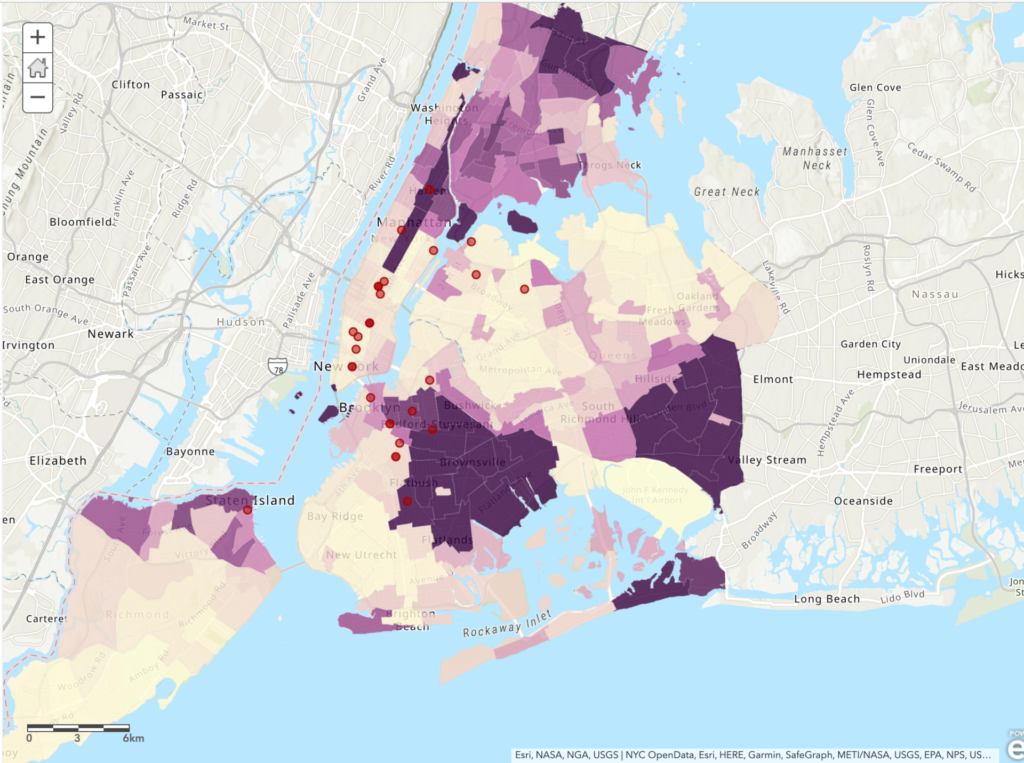

So my final proposal is about creating an ArcGIS StoryMap of the cemeteries in Manhattan in 1820 compared with 2020. I’m most interested in capturing the obliterated cemeteries—which are in all five boroughs, but the most documented ones are in Manhattan—as I find it very exciting to be mapping things that don’t quite exist anymore. In addition to providing great numerical symmetry, I think these years are also significant within the scope of my project. New York City was the largest city in the country by 1800 (then just Manhattan), and the population more than doubled between the 1800 and 1820 Census. And the most significant legislature on burial bans in Manhattan wasn’t passed until 1823 and after, so I think 1820 captures a time of great growth (and death), and it predates laws that greatly altered the deathscape. Many of these laws were passed in direct response to outbreaks (namely of cholera and yellow fever), and I think it will be very interesting to visualize how they affected the landscape of the city at a time when we’re still understanding how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting us in the present (or very recent past, as the case will be next semester).

As I was working, I was so entrenched in reading about cemeteries and finding out how my project would relate to/expand on other work in this area that I almost completely forgot about our course readings. Matt’s sage advice on rereading the proposal prompt saved the day, and I had a mini breakthrough once I started thinking about the landscape of New York in relation to our readings on infrastructure. I knew that it bothered me that there has been so much cemetery obliteration—even as part of my brain thinks that it’s not an environmentally sustainable practice and I have many complicated and contradictory questions about it being the “best” use of space—and I knew that at least some of the obliteration was purposeful, and not just because of financial interests. There are power structures that made these choices, who have built up and altered the way we live in and experience this city. And this infrastructure necessarily limits those experiences as much as it may enable them. So in mapping what has been removed, I dare to hope that my project is both an act of care and of disobedience.

Again, thank you all. It has been an utmost privilege to be in this class with you and share this experience. See you next semester!