First and foremost, I want to reiterate what others have said – this class has been so enlightening and interesting. Honestly, I didn’t know what to expect from DH and I’m so glad I decided to join this program. Thank you all (and Prof. Gold) for your ideas and openness!

I’ve been procrastinating writing this final blog post but it’s been the case all semester that after reading what my fellow classmates have to say, I’m inspired to contribute. Perhaps, it’s good that I took some time to reflect on the final proposal process. I’ve just re-read my proposal and am reminded of some of the issues I experienced when writing it. Echoing others’ comments, I had a difficult time navigating between writing a paper and a grant proposal. How much research should I be doing? – I could easily have added more pages and sources just to explain the rebus and its history. Is my writing persuasive enough that someone could theoretically want to give me money to do this project? – my proposal sounds somewhat repetitive because I was probably thinking about this too much. Are the projects mentioned in my environmental scan appropriate and relevant? – remains to be seen. In hindsight, I wish I had started this process much sooner so that I would have time to consult with others like Micki Kaufman, the other fellows or the library (great job Elena and Bri)! But, I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to write this proposal as a sort of practice for the future.

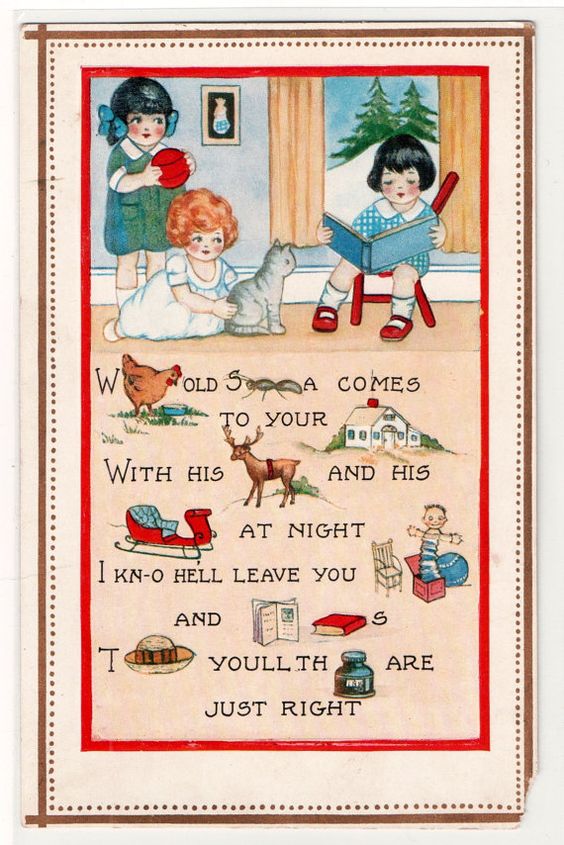

Anyway, here is part of my abstract to refresh your memory: Reading the Rebus is an online, visual archive of 19th century British and American rebus ephemera. The project aims to make a select group of historical rebus ephemera accessible in an engaging, collaborative and interactive format to scholars in diverse fields such as linguistics, history, education, communications, design studies, and visual arts, as well as members of the general public – opening up new possibilities for discovering how we see and interpret visual information. Each rebus puzzle will be treated as an interface of inquiry to conduct close reading experimentations, translations and interpretations by audience participants. Reading the Rebus challenges the notion of traditional texts by using humanistic qualitative analysis, while also contributing to the history of language and visual communication from cuneiform and hieroglyphs to contemporary, digital emojis.

And so in the spirit of the rebus, I leave you with Xmas holiday greeting!