And just like that my very first semester in the DH program is done. While this year of learning was unlike any other, I’m so impressed with how smooth it went and how easy it was to transition to remote learning. I’m thankful we have access to technology that lets us learn and continue with our grad careers. I’m also incredibly thankful to have had such wonderful classmates! Everyone is so intelligent, kind, and thoughtful, and I’m looking forward to working with you next semester!

With this final project I did feel a little overwhelmed when thinking how to piece it all together, but I also felt confident in my abilities to fill in the gaps that I didn’t already know. Because this was my first semester (and it’s been 5 years since I left undergrad) I was feeling a little apprehensive about writing a paper again. However, the final project guidelines that Matt provided were a great roadmap, and I felt better knowing that I had something to follow when getting my thoughts out. As I discovered throughout the whole fall, it was also a challenge balancing full-time work and life responsibilities with classwork. In this area, I’m actually thankful to have saved time commuting and running around the city since there’s not a whole lot we can do these days. But it’s worth acknowledging the emotional and mental stress we’ve all been put through this year, and I’m proud of us for showing up each week to share thoughts and learn while working towards these final projects. Again, I’m inspired of all of you and in awe at the project proposals you came up with. Brianna mentioned this in our last class and I’m reiterating here, I want to work on all of these projects!

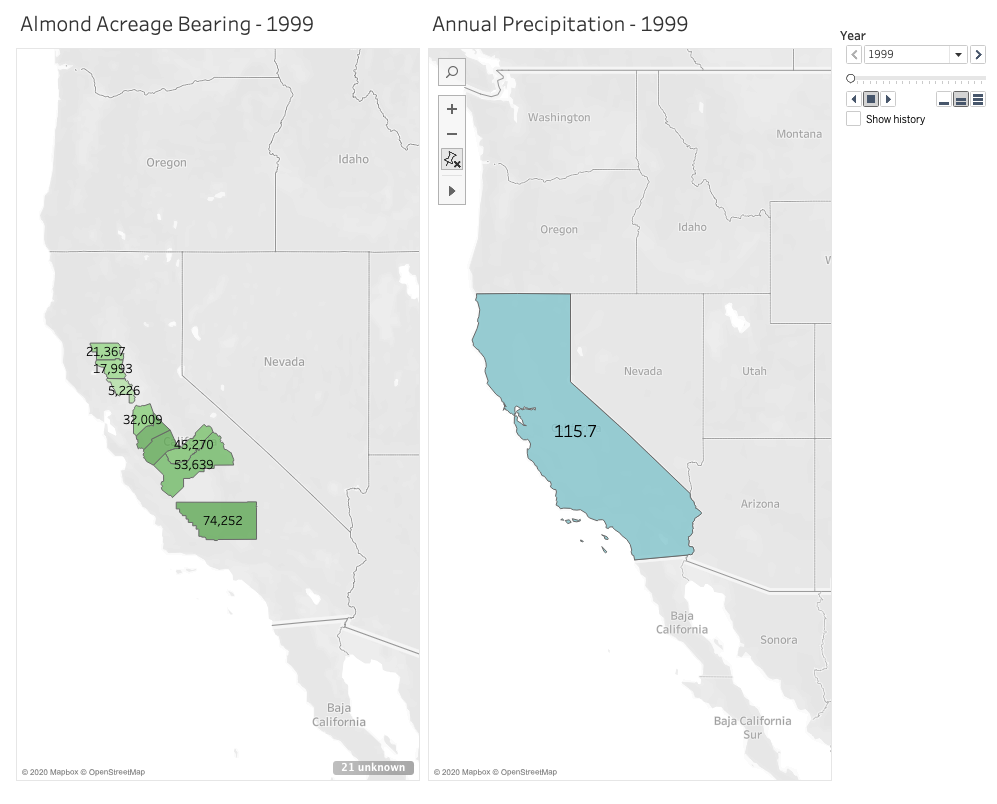

For my proposal of a tool to help farmers and community orgs have better access to the food supply chain, I was definitely ambitious. But I thought… hey, why not? I think the majority of the impact here is revealing the gaping issues that exist and prevent farmers from staying in business and struggling families surviving. So even if the problems here are just too large for any single tool to solve, let alone a proposal from only a graduate course and not some major government program, I think it’s worth doing the research to shed some light on the ways these groups are struggling. I learned so much about the complex and byzantine food supply system that currently runs things, and got insight into heartbreaking figures that reflect how many families are struggling to put food on the table. All this to say, it helps to break things into pieces rather than try to bite off everything all at once. Thanks to Matt’s notes when I initially submitted my proposal last month, I broke up the whole project into phases that could be used as stepping stones that would make up one powerful, multi operation tool, or used individually depending on the needs of the user. I think we all stumbled across this over the semester but again, scope creep is real.

Many of us also shared worries about not knowing the full tech requirements and roles to build our projects. And I think that’s OK! I know I only scratched the surface of this area while doing research for this project, and I’m excited to meet new experts and learn more about these roles in future DH classes. It can be frustrating to not know everything or be an immediate expert, but I know the learning is in the journey and we’ve only just begun. Similarly, I’m taking these DH courses only part-time and will slowly work towards the finish line. I’m jealous when I hear about the other classes many of you are taking at the same time. They all sound so interesting! I get antsy and want to bite off more than I could handle with everything else I’m juggling. But then I shift my focus and get excited about the amazing classes coming up. I hope you all feel the same way because this DH program is fascinating.

Thanks again for a great semester! Have a wonderful break and see you in the new year. Feel free to find me on LinkedIn, social media, etc. to connect!