Last month I took a seasonal dive into vampire folklore and its appearance in literature, film, and video games, thinking about the vampire archetype as it correlates to power, illness/medicine, and of course, im/mortality. (“Seasonal” in this case meaning both Halloween and political season.) As a result of having vampires on the brain, I did a quick analysis of the different spelling variations of the word vampire that I was familiar with appear in English literature: vampyr, vampyre, and vampire, to see the trends in Google’s Ngram tool. I didn’t assume that I would have such meaningful results.

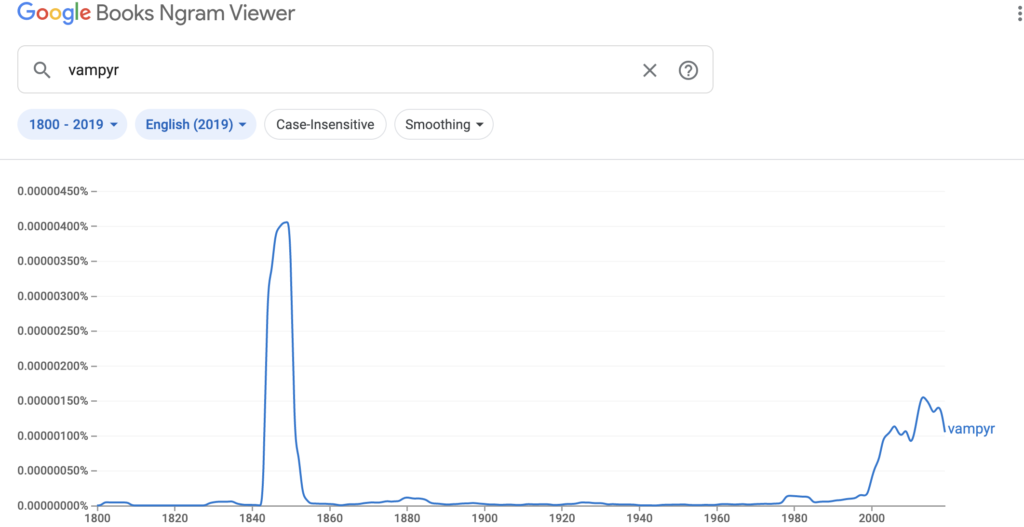

“Vampyr” alone has a clear bump in published words beginning in the late 1830s which correlates to literature about the opera Der Vampyr, and sometimes to its source material, a stage play with Der Vampyr in the title as well from a similar period. It also increases in popularity as the overall trend in vampire content increases in the late 20th century, though after reading a bit about Der Vampyr, I wonder if there’s a correlation with this spelling, and a BBC miniseries based on the opera in the 90s. Google’s tools largely return novels with “Vampyr” in their title as the source of the trend, but if I were researching the term further I’d want to know if the authors had seen the miniseries and if that influenced their stylistic spelling choice.

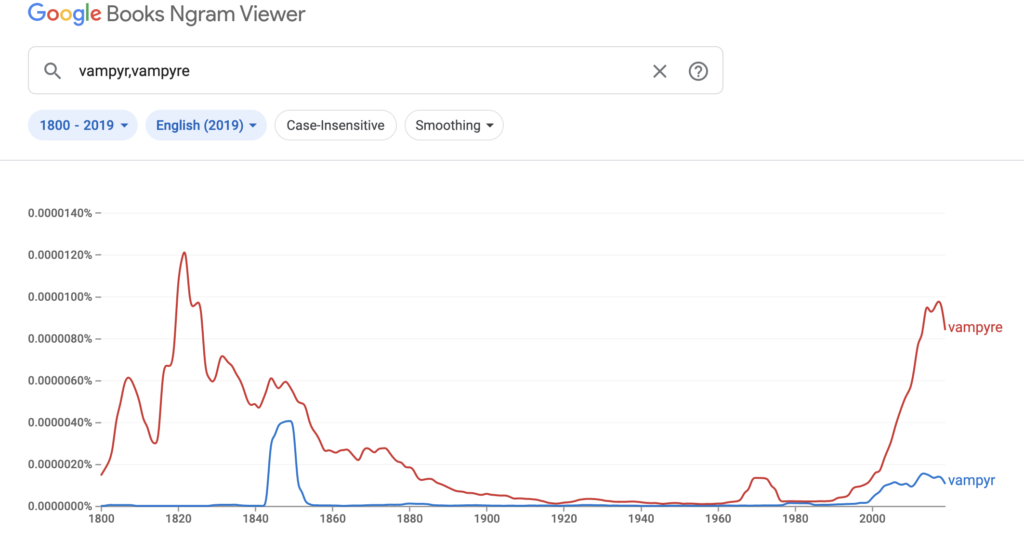

The Ngram for “Vampyre” was the richest graph I pulled as the first bump in the timeline correlates with the short story by John Polidori, The Vampyre: A Tale, published in 1819. While I was familiar with the name, I was not aware of its place in (forgive me) the vampire chronicle: Wikipedia’s entry on this revealed that not only is this considered to be (Along with Bram Stoker’s Dracula, later in the century) one of the first of the vampire stories as we know them today, but that it was also the source of the source material for Der Vampyr, the opera of the previous Ngram. More trivia: Polidori’s Vampyre was the “winner” in a contest between Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley, Polidori, and Lord Byron (who was credited with writing The Vampyre due to an attribution error for a while). Another famous work submitted to this contest was Frankenstein! Also of note from further Wikipedia diving: Byron references vampires in at least one of his poems from the 1810s as well and to be the inspiration for Polidori’s Vampyre himself, Lord Ruthven!! The literary tea from this exercise!

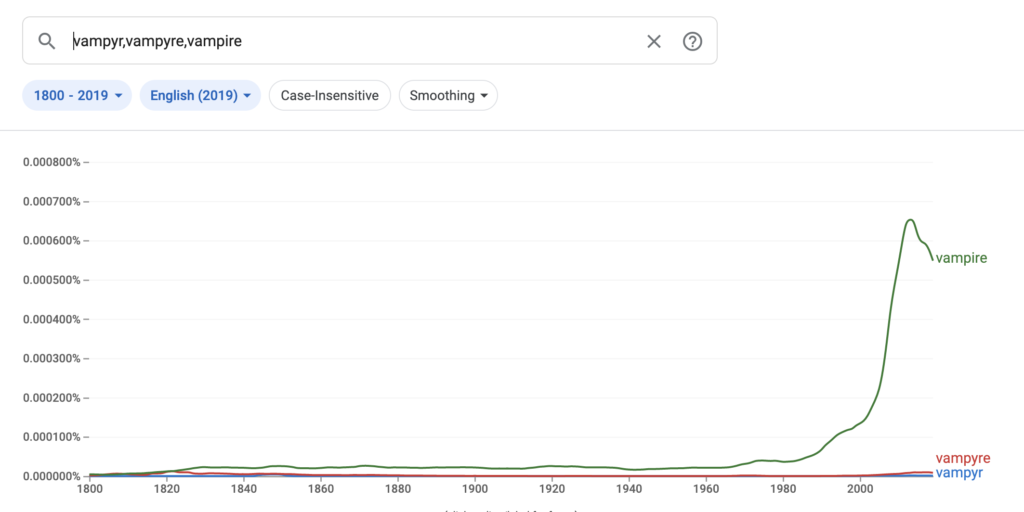

“Vampire” on the other hand, has a clear upward trending line that correlates with my understanding of the romantic vampire trope’s ascendance, and when compared, the standard modern English spelling eclipses the other two starting in the 80s. Without any further research I wonder if this correlates with the publication of Anne Rice’s series and also with the rise of another pandemic, or both. Unfortunately I wasn’t able to figure out how to hone into that specific decade, though in the search results Google gave me in the time range chosen by the tool, Rice was the most prevalent author. Many of the other books were anthologies, signifying enough content created by then to do so.

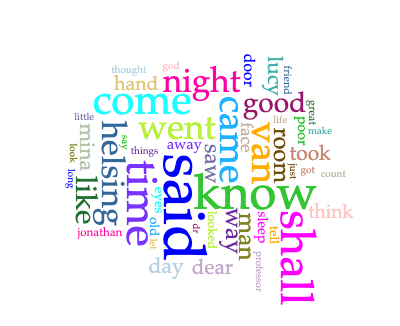

Bram Stoker’s Dracula is another small bump in the early 20th century, which inspired me to do a quick Voyant comparison between the Dracula text and the Vampyr text, as both are available to the public. This leads me to my second terrifying text analysis, via word clouds.

There were not many surprises except for one: how infrequently the word “blood” appears, since one assumes hematophagy is one of the defining characteristics of the archetype, in the way that it is one of the defining characteristics of a mosquito. Given that my exposure to the vampire archetype is firmly rooted in the 20/21st century, my bias on this characteristic may be overly influenced by my exposure to the vampire of film and television, where themes of the same genre may be weighted differently due to the way the reader/viewer perceives them. All speculative, because the text analysis tools alone cannot give me direct insight into film and television trends, but directionally it is an interesting question to ask.

I was surprised to find that text analysis, using the simplest tools I found, created such a rich study of a subject by simply inquiring. I initially had overwhelmed myself with the concept of text analysis, but I was relieved to find that with a bit of tinkering, the tools invoked a natural sense of curiosity and play, leading to further analysis. (Apologies to all for my tardiness as a result!) As an unintended result of this project, I am inspired to read both of these 19th century works of the early romantic vampire canon.

I love this Rachel! I had ideas about doing a similar search. I was curious to see if there would be a spike in monster-esque terms (monster, vampire, zombie, ghost, ghoul, etc.) in response to the First Industrial Revolution, a la Marx’s quote in Das Kapital:

“Capital is dead labour, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.”

I’m inspired to check out those books too. Thanks so much for sharing!

Very intriguing analysis! The chronology is especially interesting in the context of Raymond Williams’ examination in “Culture and Society, 1780–1950” of the interplay between industrial capitalism and the changing meanings of industry, democracy, class, art, and culture. Surely the rise of the vampire metaphor (and horror) tracks at least a couple of trends in European political economies. The first half (1800-1860) of the second graph combining vampyr and vampyre is fascinating, lending perhaps further weight to the view that early 19th century romanticism was in part a reaction to the destructive “vampirical” nature of colonial empires. Thanks!