I began this week’s readings with the Stephen Ramsay and Geoffrey Rockwell piece, Developing Things: Notes toward an Epistemology of Building in the Digital Humanities, in part because the word “epistemology” is one whose meaning I forget. At its base, we might call it the theory of knowledge. Still, in form and in its use within the academy, the word takes on a gravitas that can be confusing to this lay-person, particularly when the gatekeeping function of peer review enters into the conversation. I was surprised when I read these lines (emphasis is mine):

“Increasingly, people who publish things online that look like articles and are subjected to the usual system of peer review need not fear reprisal from a hostile review committee. There is, however, a large group in digital humanities that experiences this anxiety about credit and what counts in a way that is far more serious and consequential. These are the people …who have turned to building, hacking, and coding as part of their normal research activity.” (Ramsay)

It surprised me because I did not know there was a history of hostility by review committees to online scholarship. And also, because I have worked with digital technology for most of my working life, I know the value it can bring and the power it has within the business world. However, the tension between using a digital tool to create an effect versus seeing the tool itself as the embodiment of a theory was something I had not considered. After several readings, I came to agree with the authors that the tools we use in the digital humanities are “theories in the very highest tradition of what it is to theorize in the humanities because they show us the world differently” (Ramsay).

If the theory is a pot, then what we cook in that pot is data. Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein encourage us to see the intersectionality behind the data-points in Introduction: Why Data Science Needs Feminism. Inspired in part by the work of the Combahee River Collective, who recognized the need for a “development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking” (D’Ignazio 5), the authors seek “first to tune into how standard practices in data science serve to reinforce these existing inequalities and second to use data science to challenge and change the distribution of power” (D’Ignazio 9), albeit in the direction of greater power for people who are not “elite, straight, white, able-bodied, cisgender men from the Global North (D’Ignazio 9). That is a tall order, particularly when you consider that many available data-sets already have their inequalities baked in. An example the authors offer is PredPol. Created to assist law enforcement in determining where in Los Angeles, more police patrol was needed, it used historical data for its forecasting. However, since U.S. policing practices have “always disproportionately surveilled and patrolled neighborhoods of color, the predictions of where crime will happen in the future look a lot like the racist practices of the past” (D’Ignazio 13). In other words, PredPol created a feedback loop which amplified existing racial bias.

In Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities, Kim Gallon invites us to consider “how computational processes might reinforce the notion of a humanity developed out of racializing systems” (Gallon) and sees in Black digital humanities a mechanism to trouble “the very core of what we have come to know as the humanities by recovering alternate constructions of humanity that have been historically excluded from that concept” (Gallon). We see this put into practice by Professor Kelly Baker Josephs, when they write about the challenges they faced creating a syllabus in Teaching the Digital Caribbean: The Ethics of a Public Pedagogical Experiment, particularly ”work that directly addressed digital technology and the Caribbean” (Josephs). One of Josephs’ solutions was to enlist their students to participate in generating course content. They explain it this way, “my students’ blogging was not simply a supplement to the course; rather, it played a cognitive role in the distributed structure of the class, moving it from knowledge consumption to knowledge production” (Josephs). However, this approach was not without its difficulties, in part because the student blogs were visible on the World Wide Web and soon became primary source material for other entities. Here Josephs learned a critical development lesson; the content could be “decontextualized from the pedagogical frame that produced that work” (Josephs). As a developer, this was a powerful take-away and one that I hope we will explore more in the syllabus, namely, what rights do sources have and how should their data-sets be protected.

In Todd Presner’s Critical Theory and the Mangle of Digital Humanities, I appreciated the author’s history lessons on the development of critical theory. But what really grabbed me was their willingness to embrace the “kludge at the core of their practice” (Presner 59), meaning the work of the digital humanitarian is often messy, full of workarounds and compromises even though the product produced may appear completely stable to the end-user. It is that messiness which creates an opening for DH “to go beyond the limits and boundaries erected by prior formations of the humanities … many of which were deeply exclusionary and remain stratified in countless ways today” (Presner 61). In other words, the tools we use can reveal the world in new ways, especially when the stakeholders and contributors are understood to go beyond the academy.

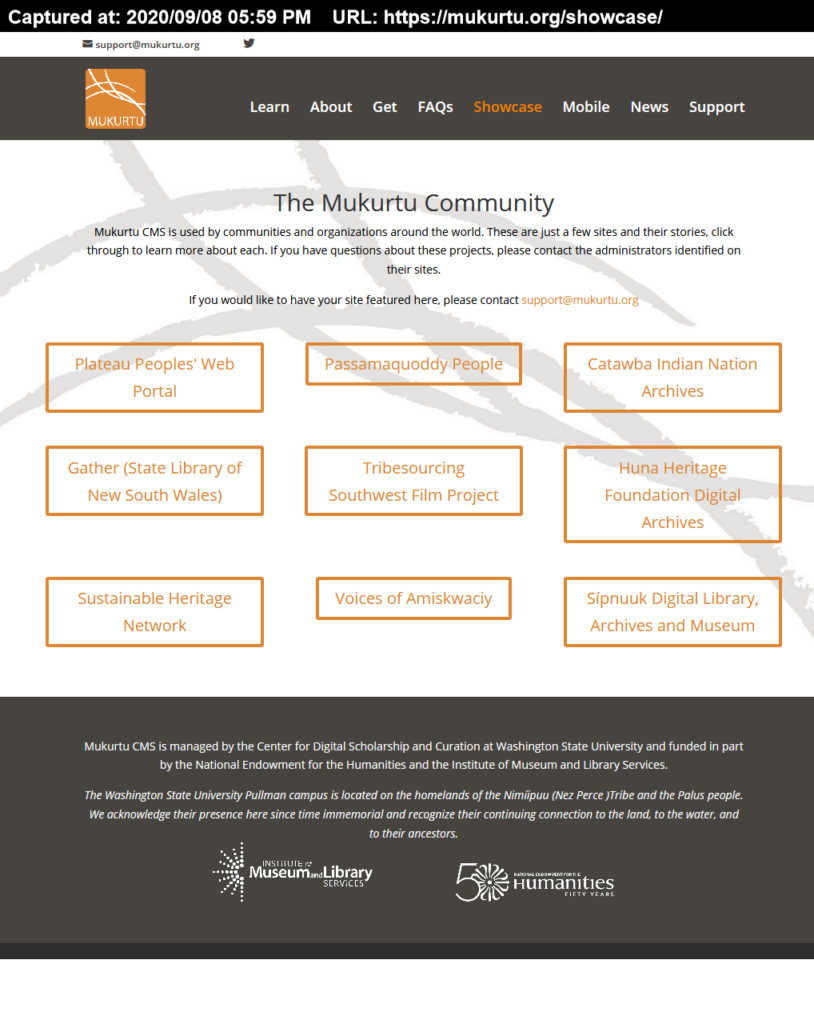

From the examples that he cited, I was drawn to Mukurtu (MOOK-oo-too), which is a content management system developed to support Indigenous communities if they want to build and share their cultural heritage digitally (Mukurtu Editors). One of the controls Murkurtu offers is the protection of some (or all) information regarding the content, depending on the needs of the community. Of particular interest was the Tribesourcing Southwest Film Project; it has collected almost 500 films, of which many were made in the mid-1900s. While the images are often true reflections of cultural lifeways, the narratives are not. This project uses the images but introduces new narration, created by members of the communities reflected in the films. The editors explain it this way: “Each film in this project will be streamed with at least one alternate narration from within the culture” (Mukurtu Editors). These are people mining artifacts from the popular culture and repurposing them to tell a different story, one that is more reflective of their lived experience.

Part of this week’s reading included visits to the sites below, so that we might get a sense of the professional culture in DH. I spend about fifteen minutes on each, so my analysis is not very nuanced. I approached it with the question: is this an organization I want to join?

- Association for Computers and the Humanities. Their website was basic in its design, just text, and hyperlinks. Its pages aren’t updated regularly; for example, on the Membership page, they advise, “As of November 2015, we have 463 members (among nearly 800 individual members of the various ADHO constituent organizations)”. Not updating your membership number for five years is not a good sign to me as a potential member; it makes me wonder what else is out-of-date. On the first read, the value here was the low dues cost and 40% discount on books from university presses.

- Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations. As an association for digital humanities associations, this site has real appeal for me. It offers a wide umbrella that can aggregate information from its organization members for the benefit of individuals. Interestingly, they do not encourage people to join them directly, but rather, join one of their constituent organizations (COs), see https://adho.org/faq.

- Humanities Commons. I like organizations that publish their roadmap, in part because it tells me what they are actually developing and where their real values lie. The HC does this. While not complete, it does allow members to up-vote on current initiatives via a Trello board. However, the HC’s primary function is the maintenance of a social network targeted at humanities scholars, where they can “create a professional profile, discuss common interests, develop new publications, and share their work.” Creating an account is free, but some material is visible only if you use an email address registered with a society that is one of its members, see https://hcommons.org/membership/.

- Digital Humanities Quarterly. I really enjoyed this site. The peer-review process is not something I have ever been engaged with, so being able to understand how it works within DH when done through this platform, was very enlightening! My only critique as a potential user is the site doesn’t appear to support RSS. As a user, I would like to be able to see alerts on new papers as they appear via a feed, so I could then follow the ones that appealed to me.

- Debates in the Digital Humanities. We are already hip-deep in this site, given many of our readings are published there. This class is my first exposure to the Manifold platform, and so far, I like it.

As a user, I will join the Association for Computers and the Humanities because of its low price-point, and because that will give me “free” access to the Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations and Humanities Commons sites. I will likely be able to get a better sense of the professional culture in DH after spending time lurking on the HC site and reading the DHC.

Some closing thoughts about this week’s readings: growing up is hard work, and it’s messy. The Digital Humanities is still at the beginning of its journey, and people like the folks in our program will affect its development over time. Openness and inclusion are wonderful concepts that are challenging to orchestrate the bigger a project becomes. I, for one, am very excited to learn more and see where the journey takes us!

Bibliography

D’Ignazio, Catherine, and Klein, Lauren. “Introduction: Why Data Science Needs Feminism.” D’Ignazio, Catherine, and Klein, Lauren. Data Feminism. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2020. 1 – 27. eBook. <https://data-feminism.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/frfa9szd>.

Gallon, Kim. “Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities.” Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016. Ed. Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016. eBook. <https://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/read/untitled/section/fa10e2e1-0c3d-4519-a958-d823aac989eb#ch04>.

Josephs, Kelly Baker. “Teaching the Digital Caribbean: The Ethics of Public Pedagogical Experiment.” The Journal of Interactive Technology & Pedagogy, Issue 13 (2018). Electronic. <https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/teaching-the-digital-caribbean-the-ethics-of-a-public-pedagogical-experiment/>.

Mukurtu Editors. Our Mission. n.d. Website. <https://mukurtu.org/about/>.

—. Tribesourcing Southwest Film Project. n.d. Website. <https://mukurtu.org/project/tribesourcing-southwest-film-project/>.

Presner, Todd. “Critical Theory and the Mangle of Digital Humanities.” The Humanities and the Digital. Ed. David Theo and Svensson, Patrik Goldberg. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016. 55-67.

Ramsay, Stephen, and Rockwell, Geoffrey. “Developing Things: Notes toward an Epistemology of Building in the Digital Humanities.” Debates in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Matthew K. Gold. Version 2.0. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. eBook. <https://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/read/untitled-88c11800-9446-469b-a3be-3fdb36bfbd1e/section/c733786e-5787-454e-8f12-e1b7a85cac72#ch05>.