Parody versus the original

On Nopvember 18th, I attended a workshop designed to teach nonfiction writers about fair use as applied under United States copyright law. The workshop was produced by the Mina Rees Library and was part of their Scholarly Communication Workshop Series. You can learn more about the series here: https://historyprogram.commons.gc.cuny.edu/fall-2020-gc-library-scholarly-communication-workshop-series/.

The workshop was held via Zoom, with eight participants, including instructors Jill Cirasella and Roxanne Shirazi. Jill is the head of the scholarly communications unit for the GC and often works with students to apply fair use to their work. Roxanne is the GC’s dissertation research librarian, which means that she works with students when they are ready to publish their capstone projects and dissertations.

The workshop was structured this way:

- We received a brief overview of fair use, including the basics.

- Review of fair use in nonfiction work

- Review of some fair use misconceptions

- Suggestions on using content outside of fair use

- Q & A

The workshop was also recorded via Zoom. If you would like to see it, contact Jill or Roxanne for the link.

Fair Use Basics

Under certain conditions, fair use is recognized by US copyright law. Here is an official definition by way of the US Copyright Office:

“Fair use is a legal doctrine that promotes freedom of expression by permitting the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances. Section 107 of the Copyright Act provides the statutory framework for determining whether something is a fair use and identifies certain types of uses—such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research—as examples of activities that may qualify as fair use” (US Copyright Office).

The doctrine permits the use of copyrighted works without permission or payment to the copyright holder. The theory behind the doctrine is that we, as a society, give people limited ownership rights to the content they create (e.g., writers and photographers and film-makers), and we give other people rights to discuss that content (e.g., like critics and scholars and reporters). There is no rigid formula we can apply to determine if fair use fits a particular incident. Still, there are four factors the courts consider when a fair use case comes before them.

- What was the purpose and the character of the use?

- What was the nature of the work being copied?

- How much of the work was copied?

- Did the copying of the work affect the use of the original work in the marketplace?

When seeking to determine if a piece falls within the doctrine, the court may ask if the material’s unlicensed use transformed it, for example, by using the content for a different purpose (like a critic doing a review of a book) or giving it a different meaning (like a researcher using Google N-Gram to determine how certain words or phrases are used within their corpus of digitized texts). In other words, the new use does not merely repeat the content for the same intended purpose as the original. The court may also consider the nature of the copyrighted work and if the new use is to support an argument.

Fair Use in Nonfiction Works

When considering using another’s work, there are four guiding principles the nonfiction author should consider. Each was discussed with examples of case-law provided.

Guiding Principle One: Critique

Fair use applies when the copyrighted material is used for criticism, commentary, or discussion of the work itself. In this use case, the entire work may be reproduced within the new work, so it may be closely examined within context. The ability to freely critique a work also protects society against intimidation. However, the doctrine expects the amount copied will be limited to what is needed to make the analytical point. Furthermore, appropriate attribution should be given to the original author.

An example offered was Warren Publishing Company v. Spurlock. In this civil case, an author created a biography of the artist Basil Gogos that included reproductions of Gogo’s artwork, commissioned for specific magazine covers owned by the plaintiff. The publisher lost their case because the court found that the “defendant’s use of the artwork to illustrate a particular stage of Gogos’ career was transformative, considering [the] plaintiff had originally used the artwork for purposes related to the advertising and sale of magazines.”

Guiding Principle Two: Proving a Point

Fair use can apply when the copyrighted material is being used to illustrate or prove an argument. Here, the material is not reproduced for commentary but rather to establish a more significant point. As ever, the amount copied should be reasonable, and it should not be purely decorative or inserted for entertainment. In other words, do not reproduce something because you like it or simply want to make your content more attractive. Instead, create a clear connection between the material being copied and the point being made.

Here the example used was New Era Publications v. Carol Publishing Group. In this case, an unfavorable biography of L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of the Church of Scientology, contained extensive quotes from Mr. Hubbard. The plaintiff argued that because the excerpts had been used without their authorization, it was a copyright breach. The court found that the biography, A Piece of Blue Sky, was fair in its use of the material because said use was designed “to educate the public about Hubbard, a public figure who sought public attention,” and [that it] used quotes to further that purpose rather than to unnecessarily appropriate Hubbard’s literary expression.

Guiding Principle Three: Digital Databases

The court has found that digital databases developed to perform non-consumptive analysis (or non-expressive analysis) of copyrighted materials is permitted for both scholarly and reference purpose. An example of non-consumptive analysis is when content is digitized, and the computer then does a textual analysis. However, this data may not be re-employed in other ways, e.g., providing ordinary reading access.

In Authors Guild, Inc. v. Google Inc., the plaintiff sued when Google made unauthorized digital copies of millions of books and then made them available to search via its Google Books service. The court found this was fair use because digitizing the material and making it public was transformative:

“Google’s making of a digital copy to provide a search function . . . augments public knowledge by making available information about [p]laintiffs’ books without providing the public with a substantial substitute for matter protected by the [p]laintiffs’ copyright interests in the original works or derivatives of them.”

Some Fair Use Misconceptions

- A maker cannot use material if their request is refused or if they received permission, and then it was revoked. Even if you do not have permission, you can still rely on fair use if your expression of the material falls within the law. In Wright v. Warner Books, Inc., the court found the defendant Margaret Walker was within the fair use doctrine when she quoted from selections of the poet Richard Wright’s unpublished journals and letters. This, even though Wright’s widow had rejected Walker’s request to use the material. The court found that the “analytic research” contained in [the] defendants’ work was transformative because it “added value” to the original works.

- A maker cannot rely on fair use if they are using unpublished material. In 1992, Congress amended the copyright act to explicitly allow fair use of unpublished materials. An example was Sundeman v. The Seajay Society, Inc. Here a scholar wrote a critical review of an unpublished novel by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, following the author’s death. “The court ruled in favor of defendant’s fair use defense, finding that the critical review was a scholarly appraisal of the work. While the paper extensively quoted or paraphrased the novel, its underlying purpose was to comment and criticize the work”.

- A maker cannot rely on fair use if they are using the entire copyrighted work. While the amount of the work copied is one of the factors considered, it is more important if there is a transformative purpose. In Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley Ltd., the author reproduced multiple Grateful Dead concert posters to show a time-line within their text. In this case, the court found that the small size and low-quality of these reproductions did not hurt the actual posters’ marketability or underlying value.

- A maker cannot rely on fair use if they are using highly creative copyrighted work. That factor is rarely decisive on its own. In Blanch v. Koons, the artist created a collage painting that included a commercial photograph of a pair of high-fashion shoes. “The court deemed the collage transformative because the defendant used the photograph as “raw material” in the furtherance of distinct creative or communicative objectives.”

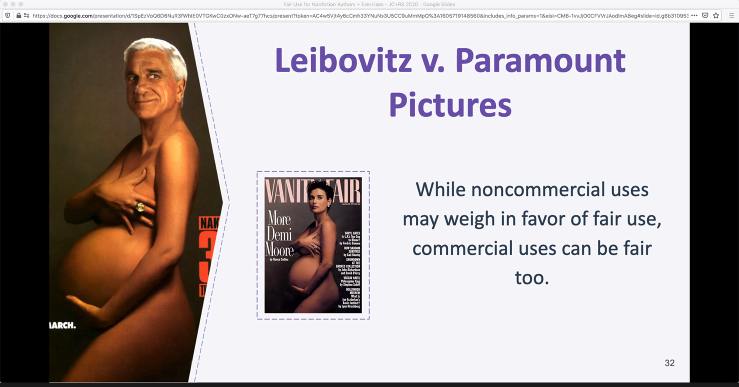

- A maker cannot rely on fair use if they are making commercial use of a copyrighted work. In Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures Corp., the marketing arm of Paramount parodied the famous nude picture of a pregnant Demi Moore by superimposing Leslie Nielsen’s face onto the body of a naked pregnant woman posed similarly to the Annie Liebovitz original. “Noting that a commercial use is not presumptively unfair, the court found that the parodic nature of the advertisement weighed in favor of a finding of fair use.”

Suggestions on Using Content Outside of Fair Use

How might we proceed if our use of copyrighted material is not intended to be fair?

- Modify the intended use.

- Ask the copyright holder for permission to use the content or for a paid license to use the work.

- Use work disturbed under open licenses like Creative Commons.

- Use works from the public domain.

Considerations Outside of Copyright

Sometimes there are contractual terms governing access to a work (e.g., archives, museums, specific databases, or websites) that can restrict your availability to apply fair use. If you are using a source with these restrictions, you have bound yourself to that agreement by using that source.

Fair use does not protect against claims based on legal rights other than copyright (e.g., privacy, rights of publicity, trademark, or defamation).

Contracts can override the native rights that you may have had to fair use.

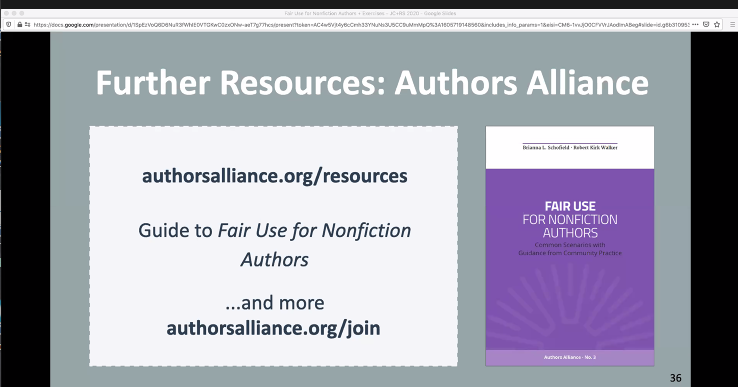

Visit the Author Alliance for more helpful resources

The Authors Alliance

The presentation was created by the Authors Alliance. Their mission is to “advance the interests of authors who want to serve the public good by sharing their creations broadly. We create resources to help authors understand and enjoy their rights and promote policies that make knowledge and culture available and discoverable”. You can find the presentation in its entirety at https://www.authorsalliance.org/resources/fair-use/.

Questions and Answers

Q: How can I be sure I can use something?

A: While a lawyer can help you determine the probability, in the end, you will only know if something is fair use if you are sued and a court decides it. Now, publishers have policies about using content based on their internal risk assessment, restricting the amount of content, etc. However, their corporate best practice is not a rubric designed by the court. It is recommended that you use a fair use checklist to test your own thinking for your own research purposes. Keep that with your research notes in case the validity of the use is ever questioned. Here are two resources:

- Mina Rees Library Research Guides: https://libguides.gc.cuny.edu/dissertations/copyright

- Columbia University Libraries Fair Use Checklist: https://copyright.columbia.edu/basics/fair-use/fair-use-checklist.html#Fair%20Use%20Checklist

Q: Are teachers covered by the doctrine within the classroom?

A: Yes. However, public presentations could be different, depending on the forum. When possible, look for images that are public domain.

Q: What about personal photos of a subject, such as those found in archives? Many biographies contain them, but they don’t always support an argument.

A: They often are included with permission, have been secured via a license, or were in the public domain.

Q: What about lifting passages with attribution but not within quotation marks?

A: Keep the quotations and show good faith with attribution within the text, as well as any footnotes.

Q: Are University Presses considered commercial presses?

A: They have different standings; some are commercial, and some are nonprofit. The entity is not the issue. It is how the work itself is being used or being repurposed that falls within the doctrine.

Work Cited

Authors Alliance. “Resources.” Authors Alliance, 6 Aug. 2019, www.authorsalliance.org/resources/.

Authors Guild, Inc. v. Google Inc. No. 13-4829-cv (2d Cir. Oct. 16, 2015). United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. US Copyright Office. https://www.copyright.gov/fair-use/summaries/authorsguild-google-2dcir2015.pdf

Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley Ltd. 448 F.3d 605 (2d Cir. 2006). United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. US Copyright Office. https://www.copyright.gov/fair-use/summaries/billgraham-dorling-2dcir2006.pdf

Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures Corp. 137 F.3d 109 (2d Cir. 1998). United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. US Copyright Office. https://www.copyright.gov/fair-use/summaries/leibovitz-paramount-2dcir1998.pdf

New Era Publ’ns Int’l, ApS v. Carol Publ’g Grp. 904 F.2d 152 (2d Cir. 1990). United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. US Copyright Office. https://www.copyright.gov/fair-use/summaries/newera-carolpubl%E2%80%99g-2dcir1990.pdf

Sundeman v. The Seajay Soc’y, Inc. 142 F.3d 194 (4th Cir. 1998). United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. US Copyright Office. https://www.copyright.gov/fair-use/summaries/sundeman-seajay-4thcir1998.pdf

Warren Publ’g Co. v. Spurlock. 645 F. Supp. 2d 402. United States District Court, ED Pennsylvania. US Copyright Office. https://www.copyright.gov/fair-use/summaries/warrenpubl%E2%80%99g-spurlock-edpa2009.pdf.

Wright v. Warner Books, Inc. 953 F.2d 731 (2d Cir. 1991). United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. US Copyright Office. https://www.copyright.gov/fair-use/summaries/wright-warner-2dcir1991.pdf.

US Copyright Office. “More Information on Fair Use.” Copyright, US Copyright Office, www.copyright.gov/fair-use/more-info.html.