This week I participated in the workshop “Open Access Explained: Best Practices for Finding Others’ Research and Publicly Sharing Yours” offered by Jill Cirasella, Associate Librarian for Scholarly Communication and Digital Scholarship, and Adriana Palmer, E-Resources Librarian, both at the GC library. The workshop was really informative, and designed to give ‘introductory doses’ for the field of Open Access. After our readings from this week, it was very interesting to then get to learn more about specific tools. The workshop introduced tools for:

- Finding scholarship and getting around paywalls

- Making you and you work more discoverable on the web

- Providing freely accessible full text of your work

- Tracking your scholarly impact

- Navigating self-archiving commissions for journal articles

The workshop consisted of three sections: the consumption and the production of OA work as well as knowing your rights as a scholar who wants to publish OA work.

The first part was about where to find OA works as a student. The easiest way to look for open access information is through Google Scholar’s Right Side Links: if the work is open access, next to the article on the right side there should be a link that directs you to the OA work. If there is no link Jill emphasized that it is not only a question of accessibility but of discoverability since the tools sometimes can’t find the information/the work, so it’s always good to use the GC version of Google Scholar as it tells you if the GC has access to it. If there is a paywall, the tool Unpaywall (extension for the browser), an open database of free scholarly articles, can provide the peer reviewed manuscript version of an article. There is another browser extension, the Open Access Button, that delivers free and legal articles instantly, and through which (if provided) you can also send an email to the authors requesting access to their work.

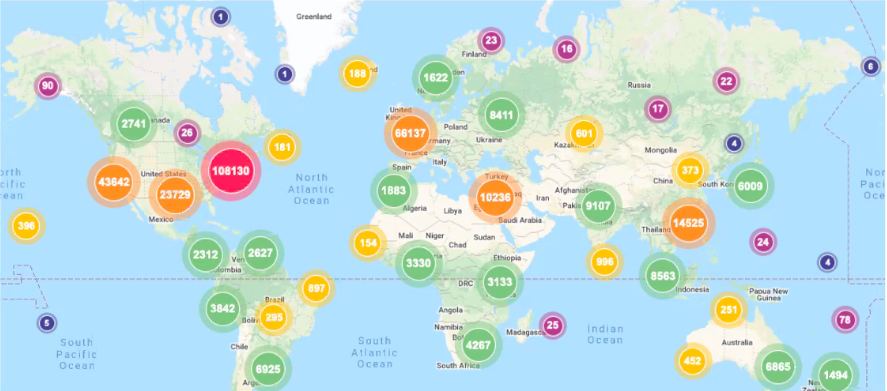

In the second part we talked about considering making our own scholarly work open access. Posting is generally allowed on institutional repositories (like for example CUNY Academic Works), disciplinary repositories (like arXis, SocArxiv, SSRN, etc.), and through Open Access via the publisher (what is considered “gold”or “bronze”OA). We focused on “green” open access: GC Publications & Research on Cuny Academic Works where you can submit your research. CAW provides an author dashboard, a personalized reporting tool for authors with works published on Digital Commons to view current download information for every work you publish as well as global insights into the sources of readership. The data is visualized as maps and statistics. I found this map of GC Publications & Research Readership since 2014 really interesting:

Jill and Amanda also mentioned to use a critical eye when evaluating resources you want to use to self-archive for public access, as some sites have a more commercial impetus for their practices than others, and this can also affect the types of services that may or may not be available to us. They also advised us to create scholarly profiles on for example CUNY Academic Commons, Humanities Commons or Google Scholar, and to follow ourselves to get alerts when we are cited. In the final part “Knowing your Rights” they addressed publisher contracts which I found very informative since I have not yet thought about issues related to that. As with most scholarly journals where you write for free and give it back for free, the reach is limited if the article is behind a paywall through the publisher. In order to share our scholarly work as broadly as we can, we should check publisher contracts, as they have evolved to give copyrights to scholars over the years but they are hard to find. Sherpa Romeo is a database for publisher and journal open access policies from around the world, giving information if you can publish your work online/if the publication allows for open access.

Thank you so much for the reminder about Google Scholar and for informing us how to access scholarly articles in a free and easy way via browser extensions. I have a question, what do the numbers represent in the visualization you’ve provided? I also found it interesting that there are still obstacles to making your own work public and respected knowledge, regarding having to obtain proposals, even on a platform like Manifold where professor Gold stores his book for our class, he likely needed to ask permission in some way to have it hosted.

Yes, I agree! found it super interesting to find out about all these obstacles for making own works public. The numbers on the visualization represent the readership of GC publications, so how many times open access GC publications have been downloaded. If you publish on CUNY Academic Works, you can also view current download information for every work you publish as well as global insights into the sources of readership in form of a visualization/map.