Text mining exercise DH70000

I chose to use Voyant as I had played around with it for a classroom exercise earlier in the term (plotting different animal imagery in Aeschylus’ Orestaia). I hadn’t loved the tool but it had confirmed my fundamental close-reading conclusions and added material to them, as well as surprising me by demonstrating sometimes the absence of what I expected to find. The results were pretty rough, as I had to rely on a collected volume in order to use the translation I was teaching for my corpus and clean up the data by narrowing it to the small relevant section that treated the trilogy specifically. I learned enough to make me decide to try it again, however.

This time, I added three texts to the Voyant search: Spanish, French, and English versions of La Monja Alférez; aka the early-seventeenth-century trans memoir of Catalina/Antonio de Erauso. The earliest edition extant remains an eighteenth-century manuscript, but the work was printed throughout the nineteenth centuries in multiple editions.

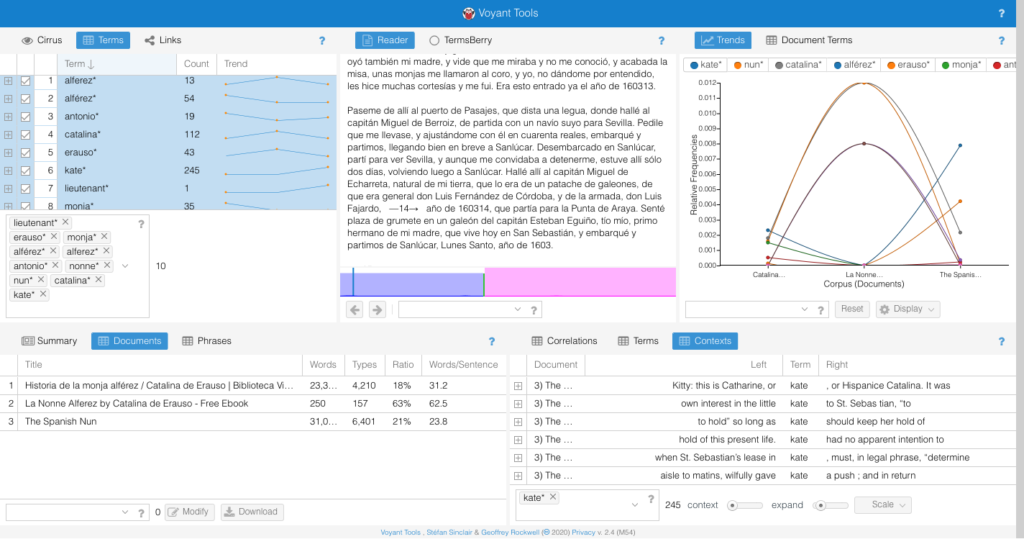

Again, I was hampered by what was available to download, but, for the English, I settled on Thomas de Quincey’s The Spanish Nun published 1853—a paraphrase or retelling, in which “Catalina” becomes a Shakespearean “Kate.” For the French I chose a late 19th-century French edition, La Nonne Alferez, and for the Spanish the Historia de la Monja Alférez, both of which remain fairly faithful to recent scholarly versions and the early manuscript.

As the Spanish versions of the work show de Erauso shifting from feminine to masculine terms when s/he travel to New Spain, originally I wanted to search for the use of masculine and feminine personal pronouns and adjectival endings in the texts. That proved too complicated for an initial run. But when I discovered that de Quincey had Anglicized de Erauso to fit a very different nationalized gender narrative, I became interested in the extent to which the works identified the author by different names and terms and where those identifiers appeared most respectively.

Results:

I found the comparison of equivalent terms in each of the works to be the most interesting information.

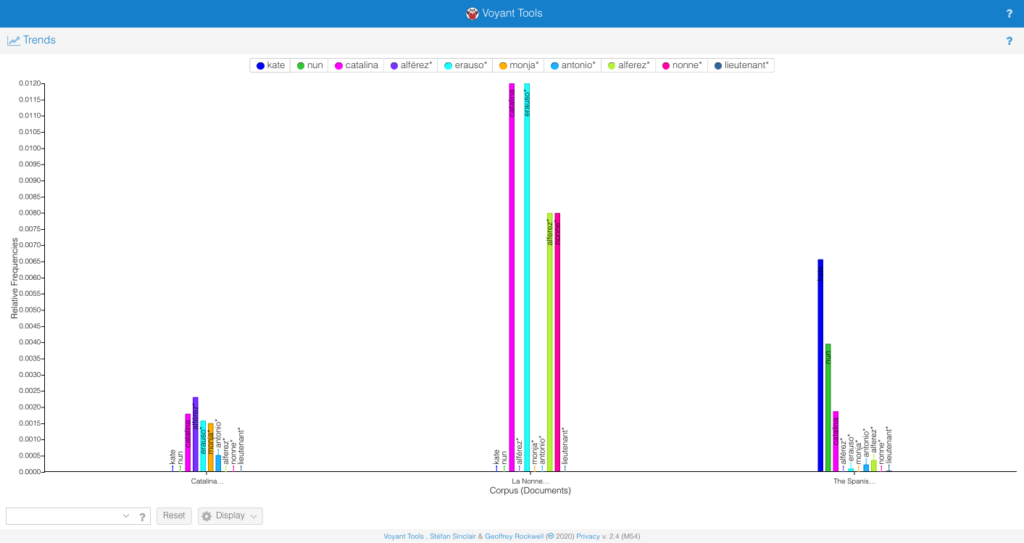

In the Spanish, “alferez” or “lieutenant” appears more frequently than any proper name or the alternative subject position “monja” i.e. “nun”; it is associated most often with “Catalina” and then with “Erauso.” This suggests an inherent gender clash or ambiguity in the characterization of the protagonist, who appears identified most often with a feminine name linked to a masculine profession.

In the French, both professional identities (“alferez” and “nonne”) are secondary and yet equal to eachother in frequency. Rather, the protagonist is identified by their first and last names and the use of alternate or masculine identifiers other than “alferez” is non-existent. It’s striking that the text uses an archaic term for nun—“nonne”—rather than the more common (and already normative from the time of Diderot’s infamous novel of the same name) “religieuse.” Equally suggestive, the text opts for the Spanish term “alferez” rather than using the more common “lieutenant.” It would be worth exploring the appearance of those terms in other novels of the period to see if this is an attempt to distance de Erauso’s character from the French associations of each term or to emphasize their status as outlandish, foreign, or other.

Lastly, de Quincey’s fairly absurd revision of the narrative not surprisingly uses “Kate” far more than “Catalina” to identify the “heroine”: I use the term intentionally as the English text pairs “Kate” with “nun” and hardly uses any masculine indicators, or even the gender fluid “Erauso” that they maintain throughout their life.

In short, the exercise was useful for identifying the extent to which the French and English translations erased the gender ambiguity of the original Spanish account, making it that much harder to recognize La Monja Alférez as an important early modern instance of a trans text.

I’m so glad you chose this text for your analysis! I remember encountering a version of this in school (maybe even as far back as high school), and I’m pretty sure it was a translation rather than in Spanish. I never would have thought to question the ways that translations would misidentify or alter their identity. So thank you!